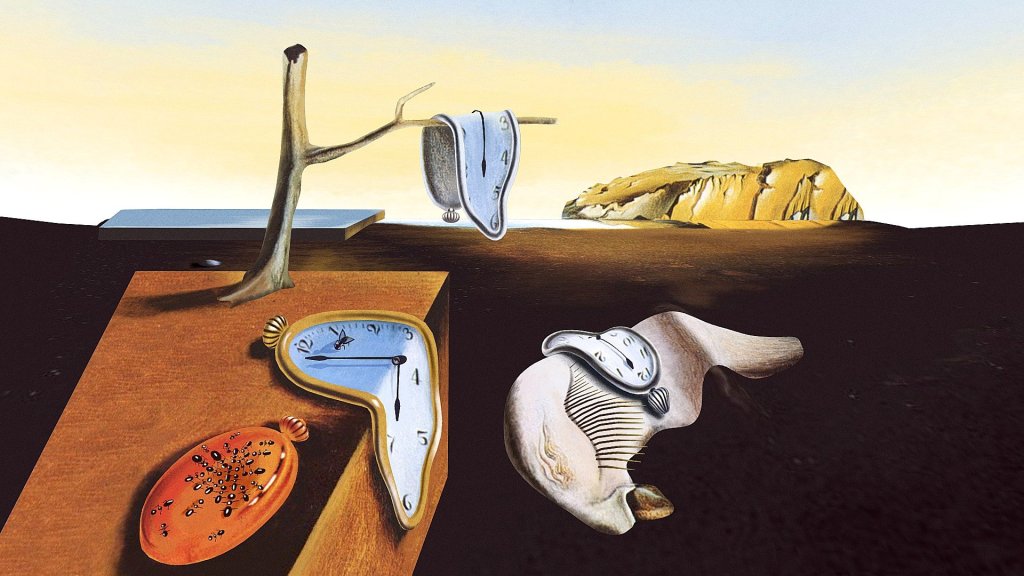

One of the places I love to visit when I go to Yucatán is the Grand Museum of Maya Culture. Each time I visit, I learn something new or pay closer attention to something I missed the last time I visited. A few weeks ago, when I visited, I paid closer attention to a note about the concept of time in the Maya culture. It explained that the Mayas understand time as cyclical. This is one of the reasons why spheres were used to mark time – the Mayan Calendar. A linear time makes no sense in the Maya culture. The future is behind us, the present is unknown, and the past is right before us. The future is behind us because we do not know how that time will be used and what it will bring. The present is unknown because it is happening as we live, and therefore, we cannot actually see it until it is in front of us. The past is clearly in front of us because we remember.

Each culture has a concept of time that works for them. Everyone knows the USAmerican adage: “time is money!” The whole USAmerican culture is fixated on this cultural reality. Although I have not studied the origins of this, I assume it comes from the Protestant work ethic. According to some early Protestant theologians – specifically, Calvinists – labor is not only honorable, but it also shows whether you have been chosen by God. People in Calvinist societies wanted to show everyone that they had been chosen, and thus, they worked hard to demonstrate that they had been chosen.

Sociologist Max Weber was the person who defined this concept. In his work, Weber argued that this approach influenced the way in which the earlier Anglo settlers of what became the USA were able to succeed. Since then, this approach has permeated USAmerican society. “Time is money” is just a different way of saying that you must not “waste” time; you must use every minute of your life on a task that is productive. Time is seen as something linear, and you complete one task after the other in a linear way, in order to be as productive as possible. You can control time, and it is a limited resource that should not be wasted. I just learned that this perspective is called “monochronic.”

According to the definition I found, “In monochronic societies, people take time seriously, adhere to a fixed schedule, and value the sequential completion of tasks.”[1] This perspective flourished during the Industrial Revolution, as it made sense for this period of history when the main goal was to produce as much as possible.

On the other hand, there are polychronic societies. In these societies “people perceive time as more fluid, where multitasking and interruptions are normal. Time aligns more with the sun, the moon, and Mother Nature than it does with the hands of a clock.”[2]

In Latin America, our societies tend to be polychronic. This, of course, is a generalization. The Protestant work ethic and the USAmerican obsession with making money have definitely influenced most Latin American societies. Nevertheless, our cultures tend to be more polychronic, understanding time in more flexible ways than European and most North American cultures (with the notable exception of México.)

When I first moved to the mainland USA, the understanding of time was one of the greatest cultural shocks. I couldn’t quite comprehend what I understood to be an obsession with timeliness, cutoff times, hard deadlines, etc. I would be flabbergasted at how little quality time people spent in each other’s company. To this date, I still cannot comprehend how many of my USAmerican friends can be exactly on time for something. I do have a theory that they probably just arrive super early and park nearby until the clock marks two minutes before the scheduled time, and then they just walk up to your door. I don’t know! I haven’t cracked the code yet…

As I spend more time in the USA – I have officially lived longer in the USA than in my own country – I have adapted to some cultural and professional norms, mores, and customs. I understand that certain people need me to show up right on time, or sometimes even a few minutes earlier. I try as hard as I can to comply with the expectations. However, culturally, I am definitely wired to see time as a flexible reality.

In my own culture, when it comes to spending time with others, it is not about “being on time” but about the quality of time you spend with someone. Since time is flexible, it is expected that you prioritize companionship more than setting up specific times to start and end. There is a running joke that Latino folk – and in my case, Puerto Rican folk – spend pretty much the same amount of time saying goodbye as the time they spent visiting with you. Of course, this is a bit of an exaggeration, but it is quite close to reality.

Since time is flexible, it also means that you can work on many different tasks at once; or have timelines that look nothing like the linear timelines that are common in corporate settings. A Latin person will most likely go back and forth between projects and within stages of that project. There is no need to follow a specific timeline because it is not necessary. You will have the product finished when it is finished, and it will be a quality product because you gave it the attention that it needed regardless of whether it was “on time” or not. This causes much frustration among multicultural groups! It is especially hard when those groups are made up of people who have adapted to the USAmerican understanding of “time is money” but come from polychronic backgrounds. In these instances, the majority USAmerican coworkers use the example of the people who follow their understanding of time to dismiss the very real different understanding of time of the others in the group.

It turns out that social scientists and researchers in the field of business have already studied these interactions. I read an article online[3] that describes project management from these different perspectives and how multicultural workgroups can manage to be successful.

I will not go into the details of that paper. However, I would like to present some of my own perspectives and understanding of how to approach this reality of differences in understanding time.

First, I think it is important to recognize that “different” does not mean “better” or “bad.” It just means… DIFFERENT! Different societies and cultures have different ways to approach time. We must understand that our own understanding of the world around us is shaped by our histories, social locations, personal experiences, and myriad other things. It is wrong to expect others to behave like me, even in professional settings. It is also wrong to assume that everyone must conform to my understanding of the world. Accept and embrace differences.

Second, it is always best to foster a culture of communication and trust in the workplace – or any other place! This will help communicate effectively when these differences show up. It also helps with setting communal expectations that are born of the collective ideas and different approaches brought in by the members of the group. When there is trust and communication, people will feel empowered to share their own understanding of time, and a good project leader will help negotiate a workflow that makes sense for the group. This brings me to the next point.

Flexibility is key. What works today might not work tomorrow. Once a workflow has been established for a project, it cannot be assumed that the next project will follow the same timeline or workflow. Good project leaders will need to go back to the drawing board and go over the whole process of listening, learning, negotiating, and adapting a new workflow that works for that group and that project in particular.

These strategies can also work in personal relationships. I understand my friends’ perspectives on time, and I honor them the best I can. They also understand my own understanding of time, and you will never see one of my USAmerican friends showing up at my house for a party at the exact time I invited them! This sounds silly, but it’s true! In my Latinoness, I think I will have everything ready by the exact time I invited my guests, but there’s always something that makes it not possible to be right on time. Thankfully, my friends understand this, and they know they should show up at least ten minutes past the time I asked them. They also know that I value their company more than I value ending a party “on time” – whatever that means in this context – so they are never rushed to leave my home at a particular time.

To finish this article, I want to leave you with a smile on your face. A few years ago, FLAMA, a Latino YouTube channel, posted a really great video titled “Perception of Time – Latino Field Studies.” Please watch it, for a laugh… and to understand better what I have just written about!

[1] https://www.spanish.academy/blog/polychronic-culture-in-latin-america-thoughts-and-facts-on-time/

[2] https://www.spanish.academy/blog/polychronic-culture-in-latin-america-thoughts-and-facts-on-time/

[3] Duranti, G. & Di Prata, O. (2009). Everything is about time: does it have the same meaning all over the world? Paper presented at PMI® Global Congress 2009—EMEA, Amsterdam, North Holland, The Netherlands. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute. https://www.pmi.org/learning/library/everything-time-monochronism-polychronism-orientation-6902

People have asked me how I’ve been able to function these past few days. It has not been easy. My parents, sister, and I had been estranged for years. When I was diagnosed with cancer, they reached out. My husband and I visited with them for the first time on December 25th for their Christmas party. We’ve been in communication ever since.

People have asked me how I’ve been able to function these past few days. It has not been easy. My parents, sister, and I had been estranged for years. When I was diagnosed with cancer, they reached out. My husband and I visited with them for the first time on December 25th for their Christmas party. We’ve been in communication ever since.

Today, as a white supremacist, xenophobe, and sexual predator took the oath of office as President, I worry about Emely and her future as a Latina woman growing up in the USA. I know I cannot protect Emely or her brother all the time. I also know that her parents’ immigration status prevents them from providing all the protections that she – both of them, my niece and my nephew – deserve. But there are some things I can do. I can join the RESISTANCE and stand up for my niece.

Today, as a white supremacist, xenophobe, and sexual predator took the oath of office as President, I worry about Emely and her future as a Latina woman growing up in the USA. I know I cannot protect Emely or her brother all the time. I also know that her parents’ immigration status prevents them from providing all the protections that she – both of them, my niece and my nephew – deserve. But there are some things I can do. I can join the RESISTANCE and stand up for my niece.

“What are you?” is, then, the amalgam of the identities we espouse and embody. These are identities that we have chosen and identities that are inherent to our being. The problem comes with the way in which the question is posed. Humans are not things. We are a very complex animal with both physiological and psychological characteristics. The integration of these characteristics is what makes us unique in the animal realm. Humans can overcome our desire to associate by tribe – or herd, or school, or pack, or whatever we call the different groups of animals that exist – precisely because we can answer the question “what are you?” Yet, the answer to this question is not an “it is” but an “I am”. In using this form of recognition of the self – something that other animals lack – we acknowledge that we are more than just our instincts.

“What are you?” is, then, the amalgam of the identities we espouse and embody. These are identities that we have chosen and identities that are inherent to our being. The problem comes with the way in which the question is posed. Humans are not things. We are a very complex animal with both physiological and psychological characteristics. The integration of these characteristics is what makes us unique in the animal realm. Humans can overcome our desire to associate by tribe – or herd, or school, or pack, or whatever we call the different groups of animals that exist – precisely because we can answer the question “what are you?” Yet, the answer to this question is not an “it is” but an “I am”. In using this form of recognition of the self – something that other animals lack – we acknowledge that we are more than just our instincts.

You must be logged in to post a comment.